Modern threat‑intelligence feeds and link scanners have made previously private links searchable by anyone, like that invoice link or the doctor’s notes you were emailed last week. This article explores this data exposure problem, and how developers can protect their applications from disclosing sensitive information when URLs are logged by security tools.

Background

Many web applications rely on a familiar pattern: generate a long, random, unguessable URL and treat possession of that URL as sufficient authorisation. We have seen this approach used across a wide range of applications. Here are just a few examples:

- Accounting apps sending invoices or statements to recipient’s email.

- Medical applications sending documents to patients.

- File-sharing platforms such as Dropbox, OneDrive and Google enabling link-based sharing.

- Invite links to platforms like Sharepoint.

A typical URL that an invoicing application sends to a recipient’s email might look like the following:

https://example.com/invoice/be688838ca8686e5c90689bf2ab

The assumption is simple: If the identifier is sufficiently random, only the intended recipient will ever access it as the likelihood of the attacker being able to retrieve the random identifier is low. This is still a vulnerability (CWE-598 and OWASP ASVS v5.0 14.2.1) that we’ve reported in penetration tests for a long time, but modern security tooling has increased the likelihood from “low”.

Today, URLs are routinely collected and sometimes published by security tooling that sits far outside the control of the application owner or the recipient. For example, Alienvault-OTX, Mimecast, etc.

Sensitive data in URLs is now a greater risk than we initially thought.

A Common Approach to Document Sharing

Consider an accounting web application that emails invoices to customers. The email contains a direct link to the invoice: https://example.com/invoice/<random-id>

From the developer’s perspective, this looks secure and convenient because:

- The ID is long and unguessable

- The link is sent to the customer’s email address

- Recipient doesn’t need to create an account to access this sensitive information

Sure, this is technically CWE-598 (Use of GET Request Method With Sensitive Query Strings); but the likelihood of leakage is low (such as an attacker gaining access to server’s web logs or victim’s email inbox, or an inadvertently shared link) and developers could accept the risk to user-experience trade off.

What happens if the links end up elsewhere?

Enter Modern Security Tooling

Modern email and endpoint protection analyses URLs that users receive in their inbox or click on. For example, some endpoint products automatically submit URLs to services like https://urlscan.io for inspection. https://urlscan.io maintains public databases of submitted URLs, and depending on the configuration of endpoint protection software, URLs may be inadvertently submitted in a way that results in them being added to that public archive.

Once the URL is in the possession of a third party and stored in a public archive, an attacker no longer needs to guess the identifier at all. They can retrieve the full URL directly from that dataset, making the randomness of identifier irrelevant at this point. Here are some examples:

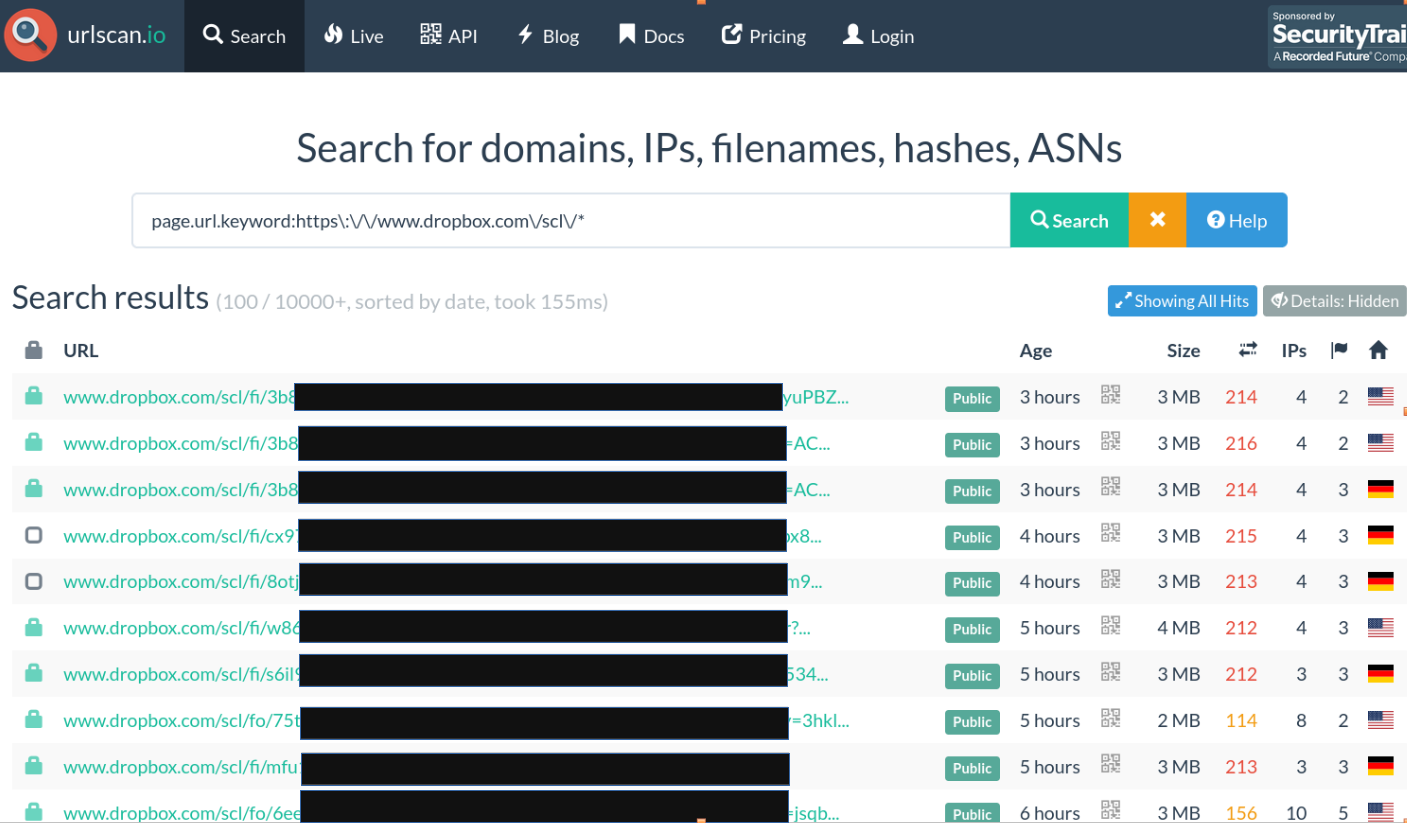

urlscan.io

A quick search on urlscan.io reveals links to “unguessable” URLs from www.dropbox.com as shown in the screenshot below.

Positive Security published an excellent in-depth blog post on how and why these URLs are ending up on a platform like this, including a bunch of examples of URLs from different services that were logged and how those could be leveraged to achieve account takeover etc. Below are some additional examples of information that can be found by browsing to these archived URLs.

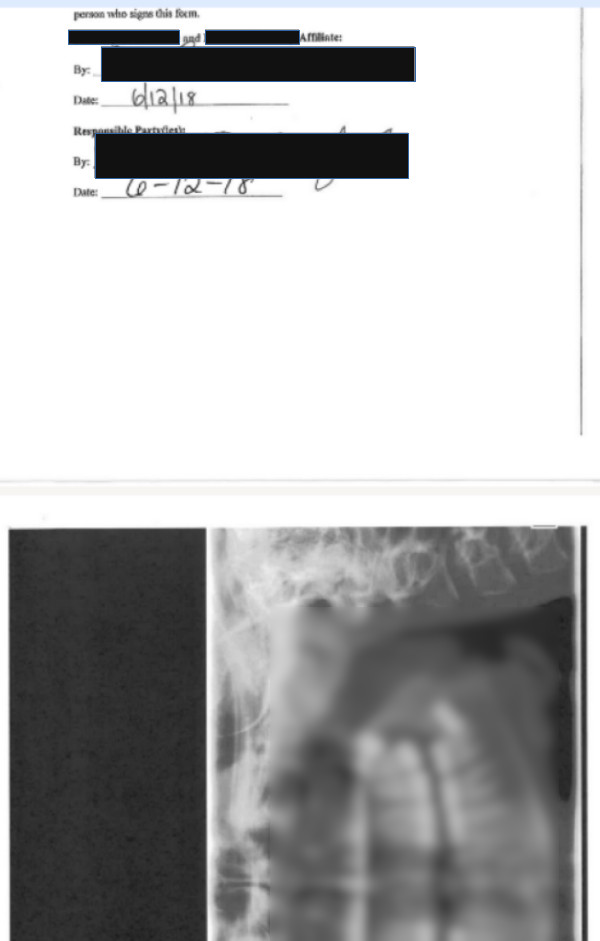

The screenshot below shows a snippet from a PDF uploaded to Dropbox containing patient details:

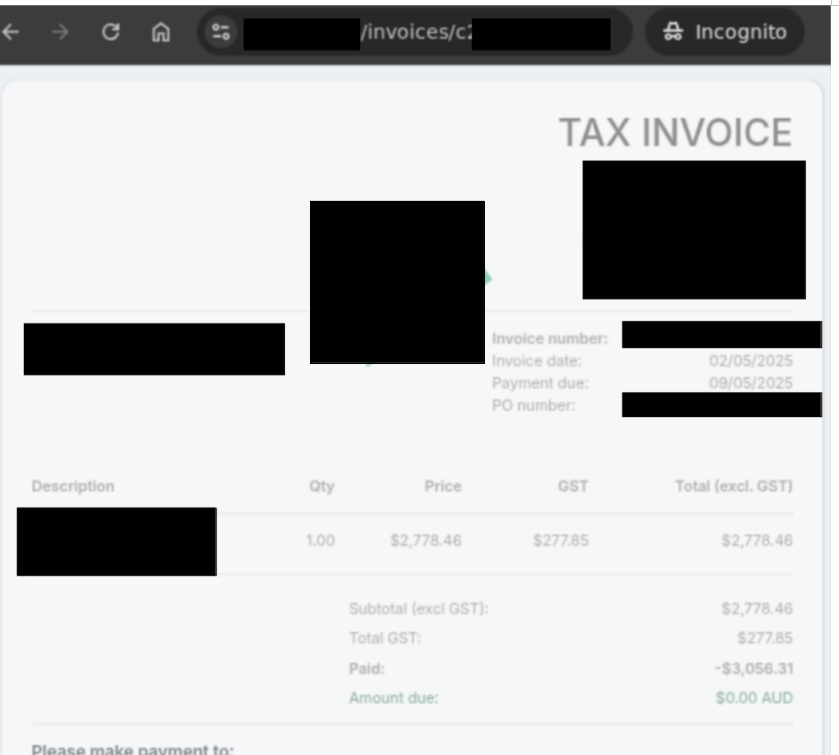

The screenshot below shows an invoice from an accounting platform.

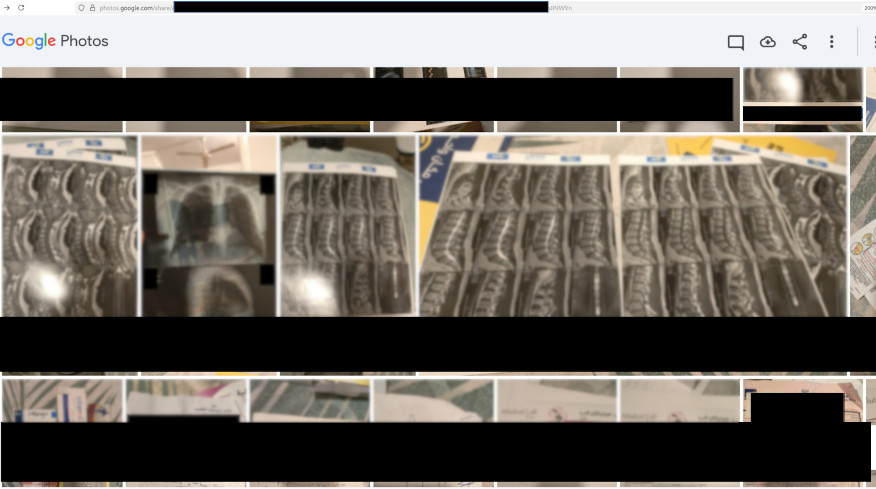

The screenshot below shows another example, a collection of medical documents uploaded to Google Photos leaked via urlscan.io:

Alienvault OTX

Surely, this is a URLScan.io issue? Well, no. Other security platforms offer similar services.

The following figure shows a curl command retrieving a list of shortened OneDrive links from Alienvault OTX:

curl -i "https://otx.alienvault.com/api/v1/indicators/domain/1drv.ms/url_list?limit=500&page=1"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 171780

...omitted for brevity...

{"url_list": [{"url": " https://1drv.ms/f/c/...redacted...", "date": "2026-01-07T02:56:05", "domain": "1drv.ms", "hostname": "1drv.ms", "encoded": "https%3A//1drv.ms/f/c/...redacted..."}, {"url": " https://1drv.ms/f/c/...redacted...", "date": "2026-01-05T22:59:50", "domain": "1drv.ms", "hostname": "1drv.ms", "encoded": "https%3A//1drv.ms/f/c/...redacted..."}, {"url": " https://1drv.ms/o/c/...redacted...", "date": "2026-01-05T12:52:05", "domain": "1drv.ms", "hostname": "1drv.ms", "encoded": "https%3A//1drv.ms/o/c/...redacted..."}, {"url": " https://1drv.ms/v/c/...redacted...", "date": "2026-01-05T08:16:27", "domain": "1drv.ms", "hostname": "1drv.ms", ...omitted for brevity...}], "page_num": 1, "limit": 500, "paged": true, "has_next": true, "full_size": 24179, "actual_size": 24179}

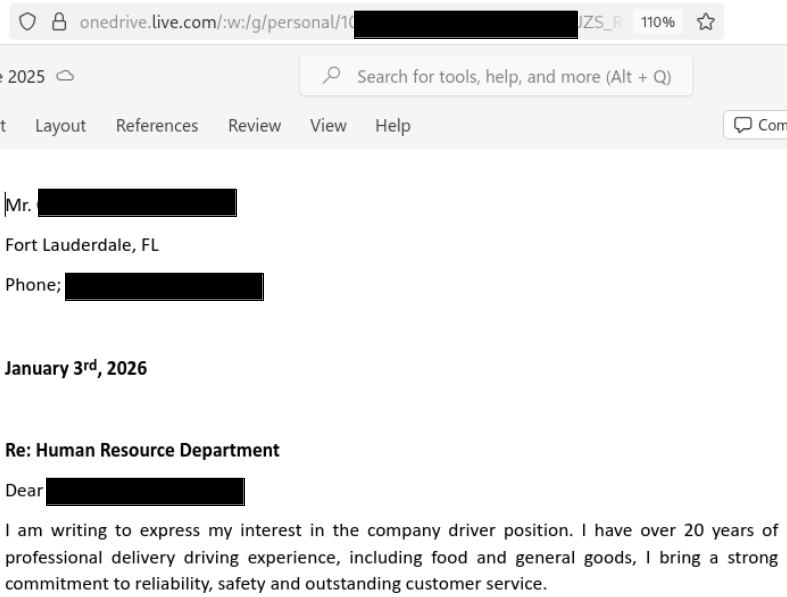

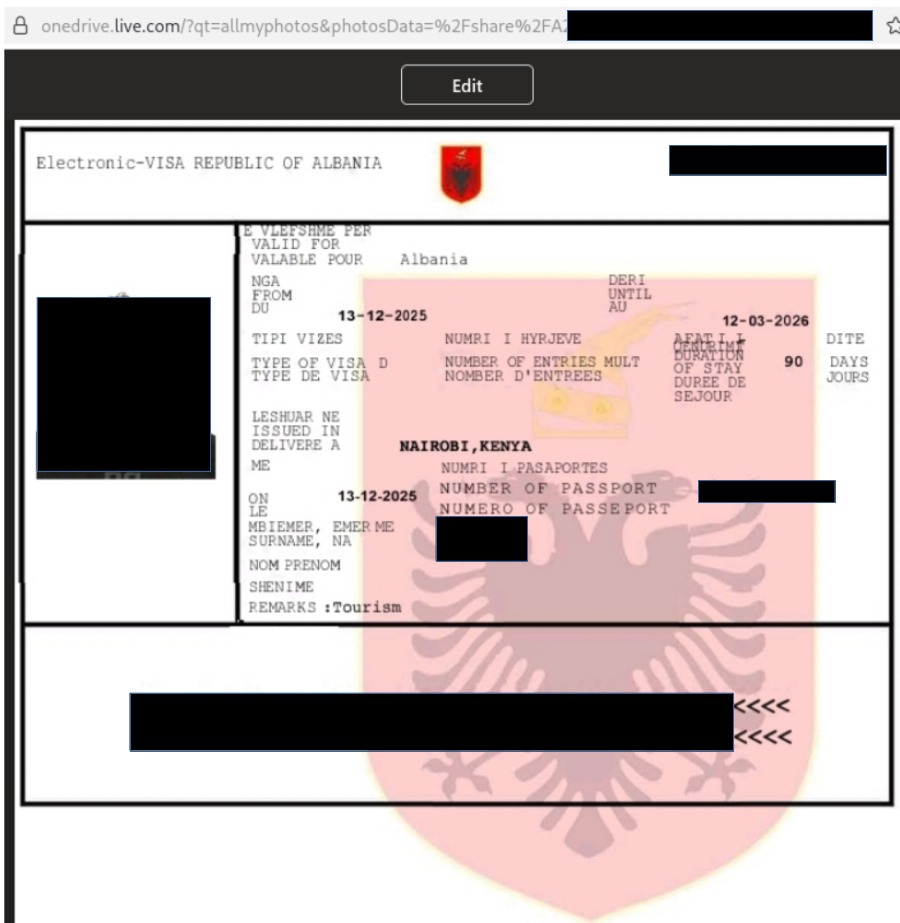

Screenshots below show some of the documents that could be accessed based on the URLs above:

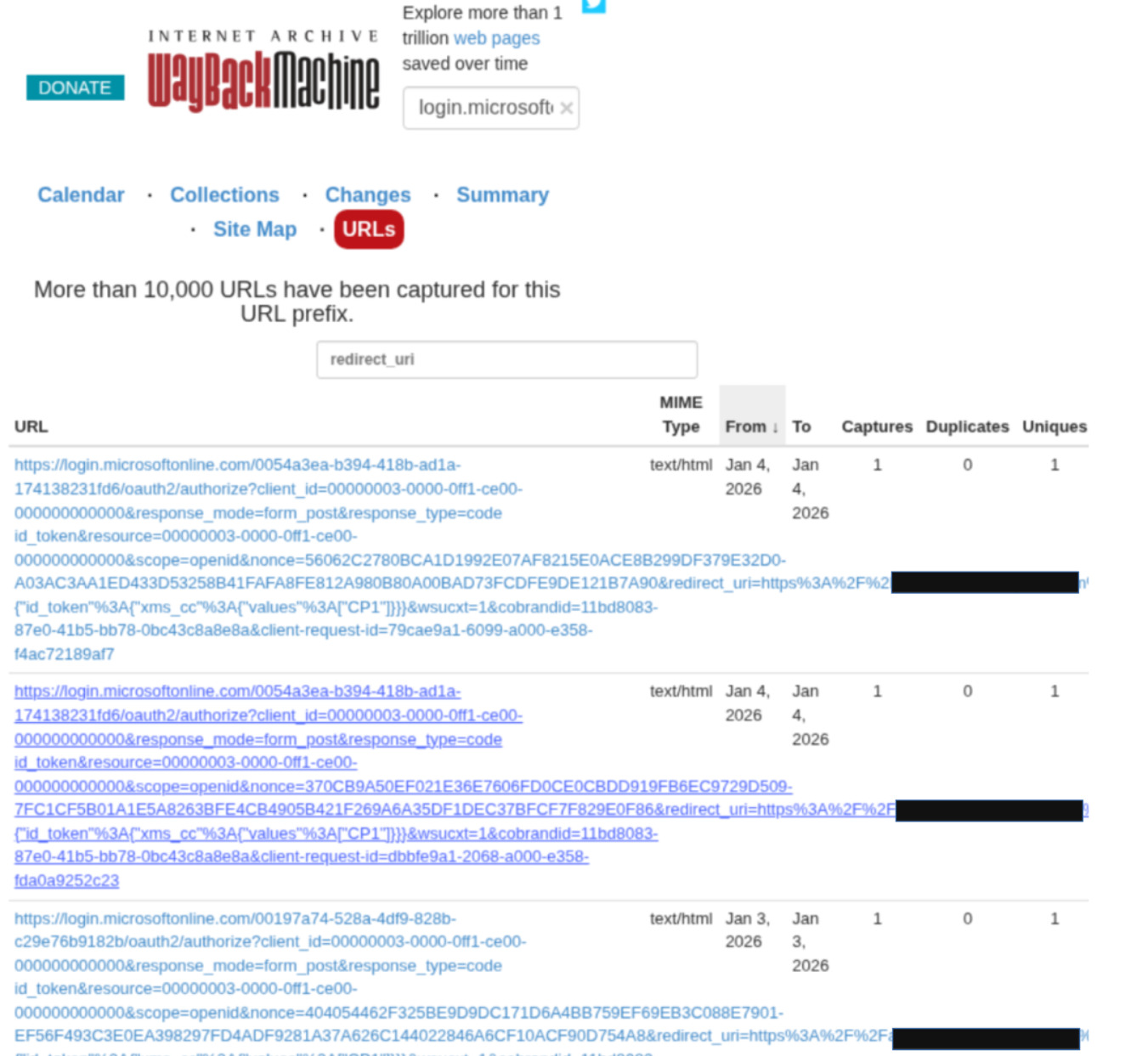

Wayback Machine

Here is yet another example, this time from Wayback machine. The screenshot below shows a search result for login.microsoft.com, and a filter looking for any URLs which contain authentication flow redirect data.

What does that mean for us?

Due to these security tools, the question is no longer only “Is this URL hard to guess?”. A better question is ”Are the URLs hard to guess, and what happens when this URL ends up somewhere public?”

We’re not entirely sure how these URLs end up in security tool public databases, logs, or archives, but practically this isn’t very important. There is always a chance that any URL can be collected and shared in a publicly accessible location by some security tooling or sometimes by the user themselves. Analysing all the possibilities for every cyber security vendor that performs URL security scanning isn’t practical. We’ve only looked at three examples, more URL scanners exist. Consider what would happen if Microsoft 365’s Outlook URL scanning dataset became part of a public product…

Instead of focusing on trying to prevent leakage, applications can be designed to ensure that possession of a URL alone doesn’t grant access to sensitive data.

How to defend against this issue

Framing this as a security tooling problem and attempting to block scanners or prevent security software from submitting URLs for analysis. This probably isn’t the best approach, since we cannot definitively say how many of these exist, how they operate, or where URLs may get leaked in the future.

We could never guarantee that URLs will never be logged or shared. A better move is to shift the focus away from preventing leaks and focusing on designing applications that remain secure even when URLs leak.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution to this problem, so we’ve listed a few approaches below. What makes sense will depend on the sensitivity of the data, the application’s threat model, and UX trade-offs. We’ll leave it to readers to take ideas from these examples and decide which combination of controls works best for their own application.

Solid solutions

1. Using existing authentication

If the link is sent to a user who already has an account, require them to log in before they can view the data. If they don’t have an account, consider prompting them to sign up first, and make sure the registration process validates ownership of the email address before the link can be used.

2. Verifying recipient email inbox access

Coming back to the invoice email example, a safer pattern for invoice delivery might look like this:

- Email containing an invoice URL is sent to recipient’s inbox:

https://example.com/invoice/view/<id> - When the link is followed, the application does not immediately show the invoice but sends a short-lived OTP code to the recipient’s email.

- The user enters the OTP and the invoice is displayed.

This ensures that the possession of the URL alone is insufficient, the user has to prove they have access to the email inbox at the time of invoice access.

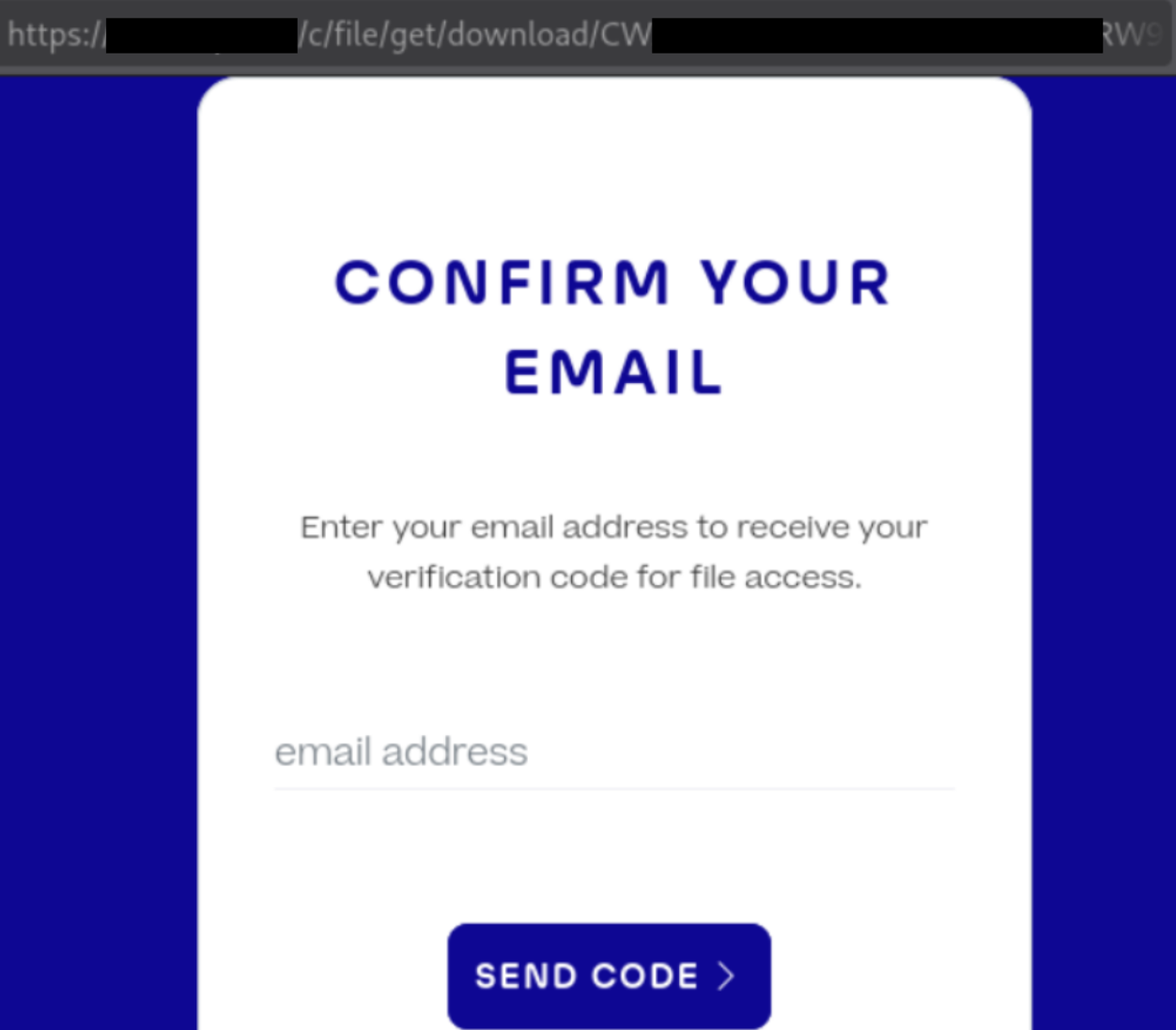

The screenshot below shows an example of this design in action from a medical application we encountered in the wild:

The user experience (UX) of this approach is poor. From a user’s perspective, being asked to wait for yet another code or link after having already received one recently feels redundant…

A more balanced approach may be to combine ownership verification with link expiry (as discussed in the “Fuzzy solution” section below). For a limited period (for example, 10 days), the link could just work. Once that window has passed, the link is treated as expired and the user is asked to prove inbox access before access is granted. When this happens the application should be clear that the link is old and that reauthentication is required to protect sensitive data so that they understand why the extra step is necessary. Reauthentication can be performed via an email-based one-time code, or via SMS. From a UX perspective, SMS often feels more intuitive because it avoids repeating the same interaction pattern (a link sent by email).

However, this balanced approach does introduce a window of exposure if a link is immediately made public and careful consideration is required.

Fuzzy Solutions

The approaches below do not address the core issue of treating the URL itself as an authorisation mechanism, rather they reduce the likelihood of successful exploitation and may be useful as in conjunction with other mitigations.

1. Expiring the link after a certain number of days

Expire links after a period of time, depending on how sensitive the data is and its use case. For highly sensitive data, such as medical records, having an unauthenticated link in the first place probably won’t be an option at all. Whereas for documents with little sensitive data, this approach might be applicable.

Deciding how long the links should last could be done by reviewing how long it takes for the users to typically take to open links, and use that data along with how sensitive the data is to inform a sensible expiry window. For example, a photo sharing link may typically be opened within three days, so expiring links after that period reduces exposure without affecting most users. Once a link has expired, the application can either require the sender to resend it or transition the user into an authentication or re-verification flow.

2. Expiring the link after a certain number of clicks

Another possible approach could be a link that can only be accessed a limited number of times. For example, multiple “secure password sharing” website links are indexed in the services we discussed. Since those links generally expire after they were viewed, for the majority of the password sharing services, we couldn’t view the content since the link had already been used.

One caveat is that it is generally better to allow a small number of accesses (for example, three or more) rather than strictly one-time use, to avoid the link expiring prematurely due to simulated clicks from email or endpoint security software. Allowing more than one access reduces the effectiveness of this approach, but may still be part of a wider mitigation strategy. You could also use a ‘view this item’ button, or some other human interaction to prevent email scanners from tripping one-time use links.

Links without a Recipient Email

There are systems, such as OneDrive, Google Drive, Dropbox, etc, where knowledge of the link is enough and there is no email address that the link gets sent to. These links can be shared via whichever medium the user likes.

Unfortunately, without a mechanism to authenticate the recipient – these sharing systems will likely remain vulnerable to URL leakage issues via modern security software.

For some applications, generating short or shareable URLs is a core feature. For example, Google Photos sharing feature intentionally prioritises accessibility and ease of use. In contrast, scenarios such as emailing sensitive documents are obviously far better suited to re-architected access controls that do not rely on URL secrecy alone.

Summary

Modern URL security scanning tools have increased the likelihood of URLs being harvested by attackers. This has, in turn, increased the likelihood of CWE-598 (Use of GET Request Method With Sensitive Query Strings) and bumped that issue from a low severity problem to a higher one. How high? Well that depends on the sensitivity of the data made accessible.

This article mainly focused on access to sensitive data; however, this issue could potentially be leveraged to achieve account takeover through OAuth replay attacks or attack password reset URLs etc. Defences that rely only on ‘unguessable’ values in URLs could use additional hardening to keep the application secure.

Today, users may assume that a random sharing URL is secure and that the only risk lies in who they choose to share it with, without realising that these links may be logged or analysed automatically. If you’re developing these systems, additional care needs to be taken and unless the data being shared is not sensitive at all, good mitigations need to be in place. Having the secure option be the default option is also an excellent way to use UX design to our security advantage.

Hopefully, this article has helped explain the issue and shed light on sensitive tokens passed in URL parameters in the modern IT ecosystem.